Caucasus

Caucasus

by Nicholas Griffin

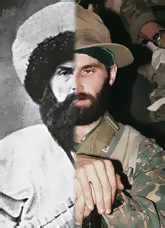

A rugged land between the Black and Caspian seas, the Caucasus is a battle ground for a fascinating and formidable clash of cultures: Russia on one side, the predominantly Muslim mountains on the other. In Caucasus, award-winning author Nicholas Griffin recounts his journey to this war torn region to explore the roots of today's conflict, centering his travelogue on Imam Shamil, the great nineteenth century Muslim warrior who commanded a quarter-century resistance against invading Russian forces.

Delving deep into the Caucasus, Griffin transcends the headlines trumpeting Chechen insurgency to give the land and its conflicts dimension: evoking the weather, terrain, and geography alongside national traditions, religious affiliations, and personal legends as barriers to peaceful co-existence. In focusing his tale on Shamil while retracing his steps, Griffin compellingly demonstrates the way history repeats itself.

University of Chicago Press, ISBN-10: 0226308596

“A complicated book, a carefully sculpted book, a disturbing book, a darkly comic book. Griffin skillfully weaves a then-and-now narrative, exploring parallels between a local 19th century Islamic guerrilla leader called Shamil and a late 20th century Islamic guerrilla leader.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Griffin wonderfully weaves historical facts and compelling characters in this adventure through the Caucasus region.” Publishers Weekly

“A near perfect recipe to whet the appetite of any vicarious traveler.”

—Washington Times

“This enthralling ride through the past before arriving in the present, through legend before fact, this deft retelling of the tragedy of these mountains conveys a great deal about life in the Caucasus today.”

—Times Literary Supplement

“Griffin is a fine writer with a sharp sense of both humor and irony. This memoir of his journey is filled with revealing episodes. This work is part history, part travelogue, and part lament for people who cherish their past but remain imprisoned by it.”

—Booklist